Cyclone Nargis forged a path of destruction for millions in Myanmar. The category three cyclone struck the nation on 2 – 3 May 2008 with winds of 215 kilometers per hour and 12-foot storm surges. It led to the loss of 140,000 lives while 800,000 people were displaced and an additional 2.4 million were severely affected. Ultimately, it exposed Myanmar’s need to prioritize strategic planning for preparedness and response to disaster events.

Nargis became a turning point for Myanmar – the cyclone was the most devastating in the region since Cyclone 2b in 1991 which claimed 135,000 casualties in Bangladesh. The nation has since made strides in emergency warning systems and shelter provisions. Their prioritization of disaster preparedness limited the impact of Cyclone Sidr to 3,000 death in 2007. A neighboring nation to Myanmar, Bangladesh proved that preventative measures are the optimal approach.

Unfortunately, weak coordination and communication networks, coupled with lack public knowledge about the risks of cyclones put Myanmar’s coastline communities in a severely vulnerable and underprepared predicament. Local non-governmental organizations (LNGOs) with links to these communities were cut out of the preparedness and response procedures, which further exacerbated the cyclone’s harm.

The unprecedented impacts of disasters lead responders to evaluate, innovate, and enact. The magnitude of loss endured due to Nargis is undeniably difficult to fully comprehend, and the immediate priority of authorities and stakeholders in Myanmar was to prevent future calamities from having the same effects. It also became clear that unified and coordinated action would only progress through a systemic approach.

Taking the Initiative

Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) initiated the dialogue to collectively and systemically respond to natural disasters following Nargis. They utilized the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) Interagency Plan Contingency Planning for Humanitarian Assistance to formulate their plan.

The organizations began by establishing the Myanmar NGO Contingency Plan Working Group (MNGO-CPWG). It consisted of a steering committee, funding board, program committee, and cluster leads. The group sought to mitigate the impacts of disasters, saving lives as well as providing effective and timely humanitarian assistance and investing efforts in early recovery. Additionally, the LNGOs in Myanmar organized themselves to align their work with the government and local populations. Their objective was to collectively prepare and respond to any potential natural hazards and meet the immediate needs of disaster-affected communities and populaces, especially when a hypothetical disaster was not large enough to mobilize a sweeping national response.

Disasters are often a point of activation and adaptation for operations. CSOs have become more involved in emergency response after Cyclone Nargis, which is evident in their growing numbers. However, better preparedness and a well-coordinated approach to emergency response call for the commitment of all stakeholders.

The CPWG took the lead in managing the progress of the NGO-led contingency plan with technical and financial support from the UNOCHA and the Local Resource Center. The group consisted of 35 national NGOs that were engaged in disaster management, and it was established to jointly prioritize the key objective of the plan. It endeavored to ensure effective and comprehensive emergency response in a future event of a disaster nationwide with a priority on the small-scale disasters that are primarily addressed by national NGOs.

The dialogue between these organizations established the next step and outline for the plan. A large consensus found that there should be a general plan in place to further delineate specific strategies for various hazards and situations at the district and township-administrative levels. These organizations primarily emphasized the importance of applying the current, more generic CP to be of more practical use at the local level. Greater utilization at these levels would require decentralizing the plan and the decision-making process. The Myanmar NGO Contingency Plan (MNGO CP) was adopted in 2010 after extensive consultation from national humanitarian organizations, the government, and United Nations (UN) organizations.

The impacts of disasters span multiple sectors and levels. This means that it requires a multi-stakeholder approach with relevant expertise and tools to reduce their risks. With this consideration, seven working groups for education, health, food and nutrition, shelter, protection, agriculture, and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) were further constituted during the workshop. A sector lead and co-lead were also chosen to supervise the review process and submit their recommendation to the CP Review and Update Committee.

The momentum of the plan was a challenging endeavor as these organizations simultaneously implemented response activities for relief and recovery in the Delta and Yangon regions.

Aligning with the Evolving Disaster Context

A constantly changing disaster landscape required the working group to revisit its official strategies. The initial plan was updated with support from and in collaboration with the Ministry of Social Welfare, Relief and Resettlement, and the Relief and Resettlement Department from the Ministry. The MNGO-CPWG also focused on the practical application of response efforts.

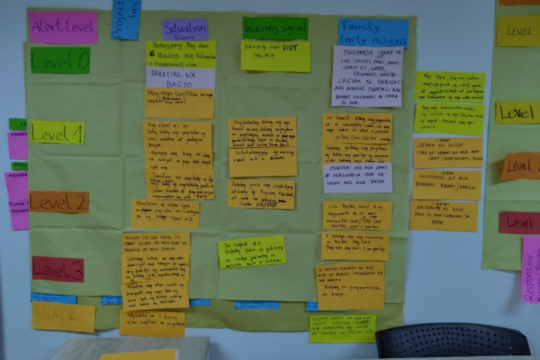

The CPWG organized a session with 42 national NGOs in February 2018 to continue workshopping the CP. The group worked together to evaluate the existing plan, hold simulation exercises (SimEx), and make adjustments. The findings and recommendations from participants were incorporated into the updated plan. These revisions included an updated emergency contact list that is constantly amended with relevant organizations involved in disaster management. When a disaster impacts a number of individuals beyond a certain threshold – 20,000 in densely populated areas and 10,000 less populated areas – the CP activates and cluster groups organized by sector roll out response procedures.

The 2018 workshop served as an opportunity to unite and build the relationship between governments, LNGOs, and international humanitarian organizations. It also provided a platform to recognize the role of LNGOs in emergency response and connect these local organizations to the international humanitarian community.

Monthly NGO coordination meetings had been ongoing between INGOS, LNGOs, and UN agencies since 2002, but they suddenly dissolved when Nargis struck. INGOs and UN agencies continued to occasionally convene without LNGO involvement. At the same time, LNGOs started to meet with each other more frequently than before. The MNGO-CP and its update workshop in 2018 boosted LNGOs’ abilities to meaningfully contribute to the disaster preparedness discourse.

The inter-Agency working groups were available to support the CPWG; the SimEx created an opportunity to build positive relationships between LNGOs and the International humanitarian community. Information-sharing with donors/INGO was weak, creating challenges in funding mobilization during disasters.

Planned Partnerships: MPP Advocates Policy Updates

Climate change has had a significant impact on Myanmar. It faces magnified disaster events and is susceptible to greater impacts from extreme disaster events. The changing disaster landscape has compelled all local stakeholders to update and consolidate their disaster policies and approach. The nation is one of five priority countries in Asia that are highly vulnerable to large-scale natural disasters. Many regions have experienced record rainfalls over the past decade; the Chin State encountering an increase of 30% and record 24-hour rainfall across other districts. The shifting forecast includes an increase in temperature by 1.3°C–2.7°C, up to 17 days of extreme heat every month, and rising sea levels of 20–41 cm along the coastline.

As climate change-induced disasters increase, the national community must constantly adapt old procedures by incorporating new solutions. The Myanmar Preparedness Partnership (MPP) organized a workshop to review, update, and implement relevant policies to address the transforming national disaster landscape in 2018. It organized a workshop to review the existing MNGO-CP to identify areas of improvement according to the changing context of Myanmar. A participatory approach was initiated under which local organizations would share their suggestions to improve the plan. This progression led to the formation of a Contingency Plan Review and Update Committee. The committee would ensure a functional plan, regroup relevant sectors for collaborative efforts, and engage working groups to respond to emergencies.

The following is an interview with Mr. Ngwe Thein. He has been a crucial member of the updating the MNGO-CP since its inception.

Ngwe Thein’s career largely focused on connecting humanitarian pedagogy into practice. He started as a trainer in Cooperative Training Schools with the Ministry of Cooperatives, Myanmar government. He expanded to international programs targeting indigenous and youth populations, “My experience with UN development projects in the Philippines and Lesotho made me realize that capacity building needs to engage marginalized communities and the future generations.

Leadership is the foundation for empowerment according to Ngwe. His interest in molding dynamic leaders pushed him to support other trainers. He returned to Myanmar when the CBI was an emerging organization. Ngwe managed workshops for skills and knowledge development professionals, “I was introduced to the Capacity Building Initiative as a resource person for an in-house training program for the NGOs and their staff. The opportunity aligned with my aspirations to strengthen the efficiency of local organizations.”

Although he is the Executive Director, Ngwe maintains that he will always be a teacher and proponent of community development, “My main profession is to enhance the capacity of those who work in the development field.” The director’s ambitions motivated a partnership with MPP, “The partnership and CBI strive to localize humanitarian frameworks aligns with his perspective on disaster management. Disaster is everyone’s business. I understood that collaboration and partnership with different stakeholders will enhance the disaster response.”

Cyclone Nargis’s havoc was instrumental in shaping Ngwe’s views on synergistic strategies for disaster preparedness, “Our collective efforts are always stronger than individual responses. We are essentially all working to reduce the impacts of disaster events in our ways. I believe my involvement in Cyclone Nargis’ response made me more interested in disaster preparedness and recovery.” Myanmar’s fractured response across districts underscored the need for a national plan. But as this plan came into focus, existing hierarchies prevented the DRM discourse from fully achieving the locally-driven collaboration that Ngwe envisioned.

Innovate and Adapt in the Aftermath

The international humanitarian community started paying closer attention and initiate a more proactive role in Myanmar’s disaster landscape after Cyclone Nargis. These organizations subsequently assumed a more active role in crafting a comprehensive disaster framework – the MNGO-CP. Ngwe’s analysis of the initial MNGO-CP draft identified the disconnect between INGOs and LNGOs in Myanmar. He determines this gap arose during the initial stages of connecting national and international stakeholders with LNGOs, “The UN had just started to outline the plan and introduced it to some of our local organizations. They wanted to ensure standardization by training CSOs and NGOs on how to develop a contingency plan.

The top-down structure of DRM implementation resulted in an ecosystem where CSOs and LNGOs with unique local expertise were excluded from the decision-making process. Ngwe observed that government policies similarly relegated CSOs, “Disaster Management Law had a very limited role for CSOs, which created a gap among the stakeholders. Although the CSOs or Local NGOs usually are at the forefront of DRR at the local level, the government could not incorporate the role of CSOs in a significant way.” Although strides were being made towards a comprehensive framework, the MNGO-CP had yet to unite CSOs with the government.

Cooperation for Policy Enablers

The MPP brought together stakeholders in a way that valued all opinions and insights a decade later. Ngwe views the partnership’s ability to serve as an inclusive platform as its fundamental attribute, “MPP is a true partnership compared to previous collaborations and partnerships among CSOs and LNGOs.” After representatives from the Foundation and ADPC met with members of the Contingency Plan Working Group (CPWG), the coalition developed more holistic strategies for engagement. “These actors prioritized inclusion. They brought the government, CSOs/LNGOs, and private sector to work on improving the capacity of local actors.” MPP’s method embodies practical cohesion between partners instead of disjointed and isolated goals. This creates an environment with less friction and more room for local actors to be elevated.

The 2018 workshop renewed the emphasis on CSO involvement in disaster management. The workshop revitalized the CP by reflecting the inputs and expertise of civil society and the private sector. In addition to refreshing stakeholders’ memories of the framework, Ngwe notes that the session institutionalized localization into DRM in Myanmar, “The workshop was a kind of reminder for the organizations about the CP since it was last updated in 2011. The focus was also adjusted from the national to the local level, meaning that the plan should be more locally driven.”

MPP’s role in building stakeholder relationships bolstered its effects on the capacities of each partner. Ngwe identifies capacity-building as a key outcome, “The coordination meeting organized by MPP with various stakeholders was an eye-opener for the partners to understand their roles and capacity for future collaborations.” MPP directly enabled new policy and strengthened DRM capacity by facilitating these kinds of discussions. Ngwe applauded the partnership for efforts to localize DRM perspectives through the efficient integration of CSOs and the private sector, “We understood the value to helped in developing focal hubs. These hubs have activated recovery networks that the Nargis response lacked.”

Ngwe acknowledges that pre-Nargis disaster response plans overtly excluded non-state actors, “Local NGOs and Myanmar NGOs had never heard of the contingency plan or disaster preparedness before Cyclone Nargis and the MNGO Contingency Plan. NGOs are now systematically organized alongside government and private sector stakeholders because of MPP’s intervention and the adoption of the plan.” Ngwe sees this development as a breakthrough, “CSOs now know what a contingency plan is. They have gained valuable insights from simulation exercises about the need to prepare for disasters. They also clearly understand their roles as the cluster members and cluster leads.”

Local voices come from within the community and can immediately respond to disasters with the best understanding of their community’s needs. Emergency operations are more efficient when these perspectives are incorporated from broader frameworks into specific approaches needed for unique national contexts.

Cover Image: Anne Richard @Shutterstock.com