Medical practitioners are risk assessors. “We handle the quality of life so our approach considers the worst outcomes with every case,” states Dr. Rehana Akhter. Millions of doctors, nurses, and technicians are courageous front-line workers in light of COVID-19 – “The possibility that my peers and I are putting each other at risk during our daily rounds has heightened a sense of alert in all of us.”

She sees every case with the same hesitancy as a new resident, “We have had to rapidly adapt to COVID-19 protocols. The current measures are unlike any we have encountered before.” Dr. Rehana is a senior consultant of the Obstetrician-Gynecologist department at the Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University (BSMMU), where she has practiced for the past 20 years.

The institute currently admits patients for treatment and operations only if they are life-threatening to the mother or child. The staff waits for COVID test results if they conclude that treatment can be delayed. Dr. Rehana would have four to five operations on a regular day- “My patients are either inflicted with complications related to pregnancy or gynecology. We currently limit admission into the hospital to pregnant women with serious complications that result in continuous bleeding and require immediate medical intervention.”

The surgeon is extra cautious after a COVID-related scare during an overnight operation: “A pregnant woman came in with excessive bleeding. We took her to the operation theater immediately. Although the surgery was successful, she did admit to being COVID-19 positive. Most patients believe that they will be denied treatment if they are positive.”

Dr. Rehana has since approached the operation theater with the presumption that the patient is COVID-19 positive, “The incident happened during the early stages of the pandemic. We now have more information and take the necessary precautions for any operation.” The hospital tries to release patients after two days of the operation. They limit one attendant per patient and house patients that need to stay longer in isolation rooms.

Bangladesh has made significant improvements in maternal health. Maternal mortality has decreased from 574 per 100,000 live births in 1990 to 194 in 2010. The numbers are predicted to improve to 87 per 100,000 by 2021. Public hospitals and the World Health Organization (WHO) are suggesting against conception during the pandemic. “Both pregnancy and COVID-19 suppress and affect the immune system. It puts many women at a much higher risk.”

Prognosis under the New Normal

The conditions of health workers are alarming in Bangladesh- 3,301 health workers which include 1,040 doctors, 901 nurses, and 1,360 technicians who have been infected in the first four months of the pandemic. Dr. Rehana maintains that their safety needs to be a higher priority, “More than 3% of doctors have contracted COVID-19 in Bangladesh. We have the highest health worker mortality rates in the world.” National hospitals are now implementing provisions to ensure the safety of these frontline workers. The BSMMU has developed a rotational duty roster to maintain health security. “Doctors are always wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) and are providing routine services outdoors. If the patient requires surgery in the coming days or weeks, we require them to obtain a COVID test and isolate themselves at home until prior to the surgery.” The country is the 16th worst affected country in terms of total infections. Testing has become a challenge as there are over 20% infection rates in the daily samples while the testing frequency has been cut by 25% between June and July.

Bangladesh has an average of 6 doctors for every 10,000 patients. The disparity is even greater in rural areas but digital solutions are creating possibilities in the remotest parts of the country. Dr. Rehana manages diagnoses and treatment through Telemedicine services, “BSMMU set up the A2i Health Care service with the Information and Technology (ICT) Division.* It has allowed me to attend to more than 20 patients a day through social media. There is a visible shift towards Telemedicine services due to COVID-19. Community clinics are now able to reach more than 6,000 people with health services.” The global telemedicine market size is currently $41.4 billion and is witnessing a growth of 15.1% in the coming decade. The Asian market is predicted to demonstrate the most rapid growth. Telemedicine has potential in Bangladesh as access to the Internet has grown by 19% per year since 2012.

The inauguration of the A2i Health Care service was momentous for Dr. Rehana. She is an advocate for medical innovation through technology, “I presented a remote ultrasound that would also monitor fetal health. A technician in Chandpur placed a plate on the mother’s stomach and I was able to see the development of the fetus.” Rural parts of Bangladesh have disproportionate health interventions. Four of the major cities with 15% of the population comprise 35% of doctors and 30% of nurses whereas 20% of health workers serve 70% of the population that lives in rural areas. “Regions like the Haor have no roads because they are inundated with floods half of the year. To provide medical interventions in these areas surpasses any expectation we could have predicted.”

Diagnosed for Learning

Hospitals serve multiple purposes during a disaster event. They are a major resource for the intake, evaluation, and treatment of victims affected. Dr. Rehana evidences this as the institute’s multifunctionality: “Hospital administrators and medical personnel have a responsibility to prepare for probable disaster scenarios in their region. They are also required to address capacity-related matters that hinder their ability to respond.” Bangladesh has a definitive gap between sanctioned and filled health worker positions with only 36% for sanctioned health worker positions. Additionally, 32% of medical facilities have 75% or more sanctioned staffers.

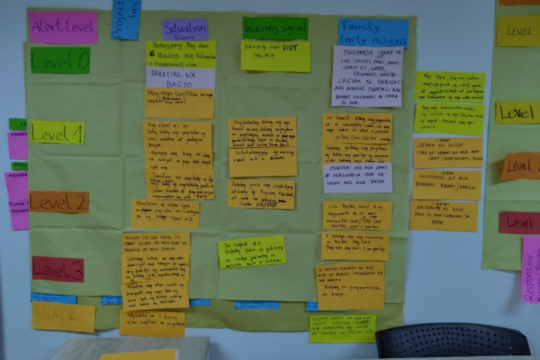

Dr. Rehana’s professionalism mirrors the school of medicine. She is constantly evolving. Her growth led her to participate in the Hospital Preparedness for Emergencies (HOPE)** course in 2015. She connects the training with a more insightful approach to COVID-19, “The course brought medical and administrative leaders and staff in hospital-based disaster management together. The parties were given a platform to discuss the principles of disaster management and develop practical steps toward preparing to respond to disaster and mass casualty events.”

The course is under the SERB and PEER programs. It focuses on supporting the Government of Bangladesh to enhance the capacity to manage any kind of emergencies. It is organized under the USAID’s Strengthening Earthquake Resilience in Bangladesh (SERB) program funded by USAID–Bangladesh. The medical practitioner found the session enlightening, “The training explained the multi-dimensional aspects of disaster events. I learned about the basic concepts and principles of health emergency risk management, epidemic and emerging infections, hospital preparedness planning, and disaster risk communications.”

She also took part in the Hospital Incident Command System (HICS) course under SERB in 2018. The course seeks to support their emergency planning and response efforts for all hazards with considerations of their size and capacity. Dr. Rehana found it to be empowering, “HICS focused on the hospital’s staff and their ability to command, coordinate, and control any internal or external emergency situations. Hospital command teams were instilled with the knowledge to create an emergency response plan (ERP).”

The HICS course centers around the operationalization of the activities of the command group and the activation of the hospital command center. Dr. Rehana commends the course’s outlook on capacity- “We learned how any health facility can optimally utilize their existing and limited resources to establish specific strategies through the incident action plan (IAP) during emergencies and disasters. It also incorporated emergency management programs, external coordination and support, and an all-hazards emergency response plan.” The HOPE and HICS courses have conducted 32 training with 769 participants between 2013 to 2019 across 12 cities in Bangladesh.

Working remotely is not an option for medical practitioners like Dr. Rehana- “When I do not go to work, I’m denying someone their right to treatment.” Front-line health workers witness the human toll of COVID-19. And they assume the roles of the everyday heroism required to combat it.

The case study was developed under the South-South facility of the Asian Preparedness Partnership (APP) and SERB. At APP, we believe in amplifying voices that build upon South-South knowledge and learning exchange. Our platforms and initiatives are dedicated to supporting countries during COVID-19.

This document was made possible with the generous support of the American Peoplethrough the USAID Bureau of Humanitarian Assistance (USAID-BHA). Prepared by the Asian Disaster Preparedness Center (ADPC) for the Strengthening Emergency Preparedness and Resilience in Bangladesh (SERB).

“Disclaimer – This study/report (Lifelines to Life on the Line) is made possible by the support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents and views of this document are the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.”

* The a2i program was developed with the Information and Technology (ICT) Division of the Bangladesh government to promote telemedicine. The service provides a helpline that citizens across the country are able to video call in order to receive medical services from specialists in BSMMU.

** The HOPE course is a 5-day residential training consisting of 23 theoretical lessons and seven exercise sessions. The course brings medical and administrative leaders and staff in hospital-based disaster management together to discuss the principles of disaster management and develop practical steps toward preparing to respond to disaster and mass casualty events.